#Verified: Dr Margaret Osborne

The calibre of people willing to jam with the Dojo still leaves us speechless sometimes... 🤷

Like Prof Gene Moyle, Dr Emma Redding, and Dr Veronique Richard, Dr Margaret Osborne has been an influential figure in our own practice and research. Where Gene and Emma are pioneering peak performance and holistic well-being in the world of dance – and Véronique in circus – Margaret is leading the charge in the music sphere.

A registered psychologist and Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Music at the University of Melbourne, Margaret straddles the applied and academic worlds with envy-inducing ease. She sets one hell of a high bar.

Here, we speak to Margaret about her personal experiences with performance anxiety, the role of self-compassion, and thoughts on virtual reality.

We'd love to start with a bit about your origin story. Can you walk us through your early days as a musician and how they've informed you today?

Margaret Osborne: I came to be a psychologist because of my own experience with music performance anxiety. When I was a teenager, I learned clarinet and classical voice. I got to the final [high school] performance exam, and way back then it was, if you knew your material, you knew your repertoire, and you prepared all the technical aspects, you'd be fine. But so much of that experience wasn't about the technical aspects.

[The exams] were at a different high school – a selective sports high school – which was already unfamiliar, and they scheduled them in the big gymnasium. If you're used to practising and performing and rehearsing in a smaller space, you're used to getting auditory feedback from the room. There was nothing. And the table of examiners was way back over there. I was over-projecting – straining – so the pitch was all off, and I was anxious anyway ... When you're performing, you're hyper-vigilant. You're paying a lot of attention to, "Am I on pitch and on tone?". You're thinking of your sound. You get caught in this self-defeating, catastrophic cycle. It was so horrible that I put the clarinet into the case and never touched it again.

In my mid-20s, I took classical singing again, and my singing teacher, Tim Patston, was doing his PhD in music performance anxiety in opera singers. I was just getting into Honours in psychology, where you have to nominate a research project, so, the synchronicity, you know? ... There was a whole gap in the literature around adolescents and music performance anxiety – there were maybe half a dozen studies at that time. And I thought, well, if young people are starting to specialise, and that's the time they're going to be facing [music performance anxiety] for the first time, we need to know more. Then, I ended up getting into a PhD.

Now, I have a dual position – with the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, teaching and researching music performance science, and also at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, training our psychologists of the future, which is a phenomenally privileged position to be in. It's awesome.

How has your relationship to performance anxiety changed?

MO: Way back then – it's becoming less so now – anxiety was something you didn't talk about. If you acknowledged it and talked about it, you'd bring it in somehow. It would manifest out of nowhere.

My relationship has come along with the acknowledgement in the discipline more broadly, in that it's something that needs to be acknowledged and addressed, and at least seen and accepted. My work now is about: don't expect to feel calm in order to perform well. It's not about being free of anxiety, and then I can perform. It's about working with and through it and reframing it as performance energy.

Anxiety is, "I am anxious". It's a whole of self-identity. So, if you think about challenging or adjusting the anxieties, that's too much of an ask because you think, "How can I? This is me" ... But performance energy is more workable. I'm very grateful I now know that [performance anxiety] can be moderated and adjusted, and strategies do work.

On strategies, where do you typically start with someone currently experiencing debilitating performance anxiety?

MO: Always beginning with education about what anxiety is, and that it has three main elements.

Music performance anxiety, for example, is a subtype of social anxiety. You don't necessarily feel performance anxiety in a room on your own when you're practising, but as soon as you're in the rehearsal space – and certainly in performance in front of people who you fear might judge you and your performance – it starts to flare up. So, education around: there's an event or situation, we have thoughts about it, which results in a feeling.

The other element, the fourth element, that's really important – particularly with anyone involved in fine motor skill execution – is the physiological response to anxiety. Particularly for musicians, it's the physical response that they want to work on because it leads to bow shakes, dry mouth, or that tight throat.

I know it's like, "Don't tell me about freaking breathing!", but I don't think people really appreciate what it can do ... If you take low, slow, easy breaths and think on the out-breath that you're reducing the level of anxiety or physiological tension to an optimal level, it gets people down into that middle range that's effective for them and the situation.

Like you, we're committed to helping actors perform at their best when it counts. You've studied several frameworks to support musicians in doing so – do you consider any to be especially effective?

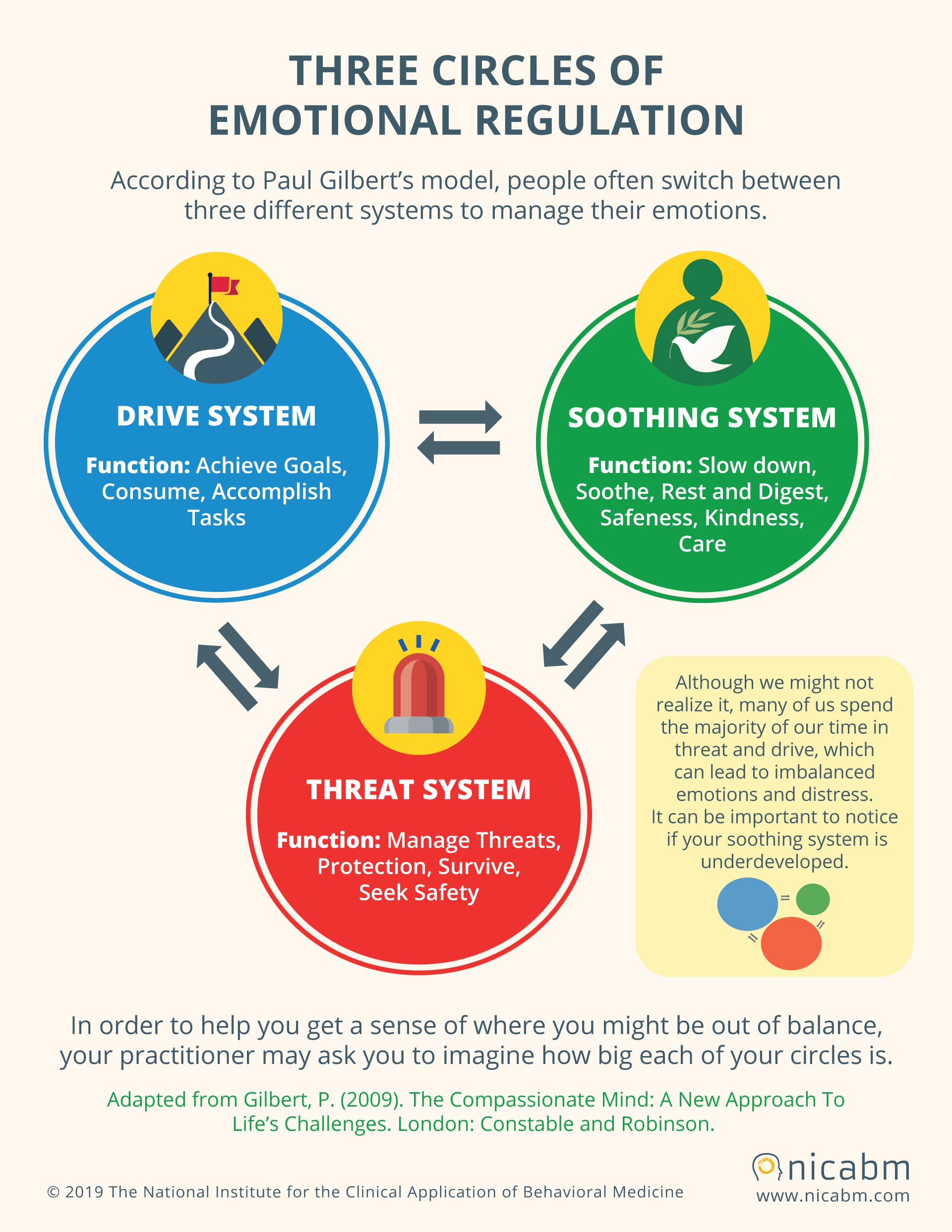

MO: I'm thinking about Paul Gilbert's work and the three emotion regulation systems. We have drive, which is just so important for artists, in particular, to achieve goals, to accomplish, to push themselves to the very limit. Then you've got the fear/threat system, and that's everything you'd expect. And, of course, the soothing system, which becomes impoverished in states of high anxiety and high mental ill health or ill-being. And then self-compassion regulates the three.

Being aware of those three systems and what you can do to balance them – and how self-compassion can do that – again, it gives people some sense of, "Oh, I can do something in response to feeling so stuck and so distressed".

Can you speak to us a little about your recent research into self-compassion and the potential implications this has for performers?

MO: It's still very much a work in progress, but we had about 200 people across music, dance, and theatre complete the first study, which was looking at a map of mental health and perceived stress, well-being, anxiety, and depression.

We know that self-compassion has a role to play, significantly with levels of depression, anxiety, and well-being. We know that relationship is robust. That's even controlling for age, gender, sexuality, alcohol use, perceptions of body image, perceived stress – it's really strong.

I'd love to give you more, but I actually don't have it yet. [However], there is a role [for self-compassion] to play in performing artists, just as we found in studies with athletes and more generally.

One of your other primary research questions – which we love – is, "How can we improve the health and well-being of musicians?". What has been a key takeaway from your work in this space so far?

MO: A musician – or any other performer – is their instrument, in a sense. They are their craft, so they have to be well, fundamentally, as a foundation before supporting the artistic. I have a four-factor well-being wheel for the individual, and when each of these four factors is evenly met, you've got balance across the wheel, and the wheel just rolls on smoothly. But if any of these four factors aren't addressed equally, you wobble. You wobble psychologically.

So, at the top, you've got work and contribution to the world. The next one across is health – physical health and mental health. The other is interests and hobbies. We need other things to refresh and gain balance about who we are in the world. This is also the difficulty with any performer where their interest becomes their work and contribution to the world. The [last] one is relationships – your intimate relationships and wider social network. Your relationships have to be solid.

The Healthy Conservatoires Network has an eight-factor model of well-being. And again, it's just [underscoring] that health and well-being for musicians – and any performing artist – is not down to one thing.

Your wheel of well-being is such a great image. To wrap things up, we'd love to briefly touch on your exploration of virtual reality. What do you see as the potential place for these tools?

MO: The work we've done so far has used a public speaking app called Ovation through the Oculus head-mounted devices. There's one scenario in it which is a concert hall, actually mapped off the Sydney Opera House, which is pretty neat. So, we've been testing the viability of virtual reality as a simulation activity for more high-stress, socially evaluated performance contexts for musicians.

We started [this research] back during COVID when we were all off campus, and the core question that started this whole thing was, "How can we get our students to practise performing in performance halls when they're stuck at home?". Even though we're now out of lockdown, it's still, "How can we benefit their performance practice in some way? How can we give them a valuable approximation of the real thing?". And the initial results are that it's really working to reduce anxiety and increase performance confidence.

Margaret's qualifications: BA (Hons) Psychology, Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology).

Big props to Margaret for her time. You can learn more about Margaret's work here and say hello on X. If you do reach out, be sure to let her know you’re a Dojo friend 👊